- Home

- About Us

- The Great Charter

of Bury St Edmunds - The Magna Carta

- The Pageants

- Events

- Past Events

- Resources and Links

- Photo Gallery

- Rebecca’s Magna Carta Blog

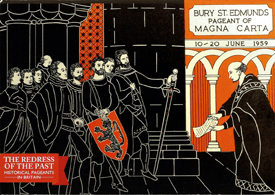

Pageants Exhibition at Moyse’s Hall 4 May to 28 August 2015 FREE

Rebecca’s Magna Carta Blog Part 7

Crisis at the Abbey

*much of the information for this post comes from ‘Bury St Edmunds, King John and The Magna Carta Crisis’ by Ken Burrows

The Abbey of Bury St Edmunds in 1210 was incredibly powerful and Abbot Samson was an influential figure, although not as popular with King John as he had been with King Richard. However, in 1211 Abbot Samson died.

The death of an abbot meant that a new abbot needed to be elected, given Papal consent and accepted by the king. It also meant that up until this had been done the revenues of the abbey reverted to the crown, in the same way that revenues of a baron’s landholdings did until the heir was confirmed. What didn’t help was that in 1211 England was under Papal interdict, which meant that religious services, except infant baptism and death bed last rites, could not take place. This also meant that they could not congregate to elect a new abbot.

In early 1213 King John reached an agreement with Pope Innocent III and the interdict was lifted. Now the monks at Bury St Edmunds could get on with the process of electing a new abbot. However things did not go smoothly. There were two main candidates; Robert of Gravely, the Sacrist and a young monk from the Cellarer’s department, Hugh of Northwold.

Robert probably felt that when the time came for the monks to offer their choice for consideration to the king, his name would head the list. Like the previous abbot he was from the important Sacristy, the monks' department dealing with architecture, buildings and maintenance both in the abbey and in the town of Bury. Under Abbot Sampson the abbey building programme had at last been completed after more than a century of activity. Bury Abbey was now seen to be one of the noblest examples of Christian architecture. Unfortunately, Robert was distrusted by many of the 65 monks because they felt that the Sacristy had for too long been taking precedence in the affairs of the abbey, against the traditions of the Benedictine rule they followed at Bury.

It was traditional to send the king a list of three choices for the position of Abbot. However, the monks voted on a radical new procedure and instead of sending three choices to the king they sent only one name and it wasn’t Robert’s. Hugh of Northwold was elected by the majority of the monks on 7th August 1213 as their choice. He was a young monk from the Cellarer’s Department who had joined the Abbey in 1202.

When King John was informed that the monks of Bury were offering him only one choice of candidate he was irate, the appointment of a senior abbot was an issue of great importance in the affairs of Church and State and the king needed to ensure that he had advisers he could trust. In the case of Bury it was the shrine of the patron saint of England (until St George displaced him after about 1300). The powerful Benedictine abbey administered wide-ranging territories in East Anglia, England’s most thriving region at the time and King John didn't trust the Bishop of Ely with his domains stretching across Cambridgeshire to the west of the abbey’s lands. King John understandably wanted to get his way in the appointment of the abbot here. He reasoned that even his father with the blood of Thomas Becket on his conscience, had been offered three choices of candidates before he appointed Sampson as abbot back in 1182. Now in 1213 John felt he should be given the same choice.

Consequently, King John rejected the monks' candidate Hugh of Northwold and he refused to recognise their election of this monk. Archbishop Langton and the other exiled bishops had only just returned, following the king's agreement with the Pope. Even at that moment they were meeting with the discontented barons in London. It seemed as if John's recent reconciliation with Rome might be put at some risk by the Bury affair.

Once news of the king's rejection of Hugh of Northwold became known Robert de Graveley and his supporters felt their unease over the way in which the election had been carried out had been justified. Robert bitterly criticised the actions of the Cellarer Peter de Worthstead and the other radical supporters of Brother Hugh (Jocelin of Brakelond was one of these 36 ‘radical’ monks). What made the quarrel particularly serious was that the two sides were by now more or less evenly divided.

Hugh’s election remained contested by King John until on 10th June 1215 he accepted it and it gained papal consent at about the same time. Once these had both been granted Hugh of Northwold officially became Abbot of Bury St Edmunds and was able to take full control of the Abbey and its lands.

It is because of the lack of an abbot with papal consent and the acceptance of the king that makes the Abbey of St Edmunds such an appealing option as a location for the barons to gather to agree what demands they would make of King John and to swear their support to each other and the cause. The abbot played the same role as a baron within his territories; he was the king’s representative, responsible for handing out justice, holding criminals and collecting tax.

It cannot be a coincidence that King John acknowledged Hugh’s appointment five days before agreeing to Magna Carta and that Hugh is listed as a witness to the document. Hugh had good reason to support the rebel barons and much to gain from the Magna Carta, especially clause one which insisted upon the freedoms and liberties of the English Church.